#71 September 25, 2025

Togo Murano and the Architectural Grounding in the Earth

I was recently contacted by Atsuko Murano-Abalos, an artist who is the granddaughter of the great architect Togo Murano. I met her at the symposium “On the Architecture of Togo Murano” that was held in February at The Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris (Japanese Culture House of Paris), and I still vividly remember the peaceful waves in a beautiful video of the ocean in Saga Prefecture that she showed me which was taken from the site where the original home of Togo Murano once stood.

She contacted me this time to ask if she could read my theory of Murano, “Things That Are the Extreme Opposite of Products,” at a lecture (on Sept. 11) that Atsuko was to give at the Yatsugatake Museum of Art, a masterpiece of Murano. There has been discussion on the future use of this museum, including its demolition, and she recalled something that I wrote about the Yatsugatake Museum of Art, and wanted to use it as part of her strong appeal concerning the importance of this building.

The focus of this essay was Murano’s advocating the “Reconnection of Humans to the Earth” to replace “Disconnection from the Earth” proposed by Le Corbusier. I felt that the Yatsugatake Museum of Art which appears to have “sprouted” from the earth in a forest best represented this “Reconnection”, and promoted discussion of this.

The reason that I have insisted on transforming architecture from “Disconnection to Connection”, and continued to put this into practice in my work, consists of my view that the age of “Disconnection” was one in which architecture was considered to be a product which is bought and sold, and an age in which architecture can be easily thrown away without giving this action much thought. The Yatsugatake Museum of Art is architecture that is symbolic of this anti-disconnection movement, which should be taken care of over the long term in the same way that we all must continue to live together and in harmony with the earth.

──────────

Things That Are the Extreme Opposite of Products

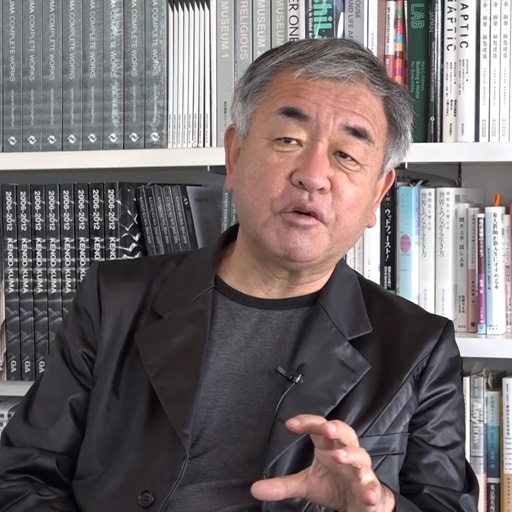

Kengo Kuma

When reflecting on Murano’s architecture, I sometimes find myself arriving at unexpected places, unexpected conclusions—and the realization startles me. I begin to wonder: Can such a conclusion really be valid? It makes me hesitate, surprised at my own thoughts. I had meant to consider the works of an elderly master known for his subdued elegance, yet before I realized it, my thoughts shifted toward radical questions: What was modernity? What did modernization mean in architecture?

Each time I set off on this small journey of thought, the same image inevitably appears at the opposite corner of my mind’s screen, across from Murano’s architecture: a blunt white box. It is none other than Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. That white house, hailed as the greatest masterpiece of modernist architecture, why does it strain so insistently to float above the ground? Le Corbusier offered explanations—that the damp site required elevation, that automobiles needed to turn beneath the building—but no matter how many times I visited the site, I could not shake the conviction that the house would be far more comfortable if it touched the earth directly, engaging in conversation with the ground. And yet, it was precisely this remarkable suspension that earned the villa its title as the supreme work of modernism. Murano, by contrast, sought to fuse architecture with the earth. I recall now the peculiar details at the meeting point of soil and structure in his Japan Lutheran Theological College and the Yatsugatake Museum of Art. I recall, too, that singular detail at the Shin Takanawa Prince Hotel, where the red carpet leading toward “Hiten” slowly gathers a whiteness, as though the wall’s material had spilled by accident onto the earth, until—almost imperceptibly—the carpet itself metamorphoses into a luminous white wall. Why did Le Corbusier go to such lengths to sever architecture from the earth, while Murano persisted in melting and binding them together?

When I learned that Murano had taken special interest in Marx’s phrase “The commodity makes a leap fraught with risk,” many mysteries seemed to unravel. To put it simply: before modernity, things did not need to make such perilous leaps. Once a thing was made, the patron accepted it. There was no risk; no leap was necessary. But in modern times, such leisurely circumstances vanished. One had to manufacture standardized products in quantity. And there was no guarantee these products would sell, no assurance anyone would take them up. It was indeed a life-or-death leap. Perhaps in the long term, from a bird’s-eye view, supply and demand “should” meet somewhere. But for those on the ground, engaged directly in the act of making and selling, no such guarantee existed within the very locus of exchange.

Le Corbusier chose to affirm this harsh reality. Architecture too, he believed, had to become a standardized product, acquiring enough fluidity to deserve the name of a commodity. To that end, he pursued simple geometric forms, standardized dimensions through the Modulor, and, like home electrical appliances sold in department stores, he severed architecture from the ground, disguising fictitious fluidity through the power of design. His early career was devoted to this aim, culminating in the Villa Savoye.

Murano, by contrast, though he lived through that same stark and unforgiving age, chose deliberately to walk a path directly opposed to Le Corbusier’s. Precisely because it was an era in which all things seemed to dissolve into the fluidity of commodities, Murano held that architecture must turn the other way, binding itself ever more inextricably and inseparably to the ground. His life became the effort to embody this conviction not in words, but in architecture itself, and to persuade others by means of that very materiality. And this was no mere act of resistance against the currents of his time. It stemmed from his conviction that architecture, by its very nature, can never truly become a commodity.

Behind this conviction surely lay the architectural culture of Japan, especially Kansai. A house, after all, was never something to be bought or sold. Instead, it was a living entity, continually adjusted and repaired by the resident carpenter who came and went. If commodities are defined by the point-like instant of sale and purchase, then architecture, in contrast, is defined by a temporal structure like an infinite line. Murano learned this from Japan, from Kansai, and embodied it.

Seen from today, Murano’s contrarian stance appears less as a nostalgic return to Japanese tradition and more as prophetic. In the 20th century of mass production and mass consumption, standardized products indeed had to make leaps fraught with risk. Yet today’s refined marketing, technologies that enable small-lot, multi-variety production, and the diversification of consumer behavior point toward a situation where commodities are no longer forced into such perilous leaps. We are now in an age in which the economy no longer pivots around “things = commodities” but around exchanges of elusive entities—financial instruments, brands, corporations themselves, and even fragments of the city. Within this shift of the economic system, our relationship with the small things once called “commodities” is also changing significantly. The “small commodities” now occupy a slower realm slightly outside the economic core, where their diversity and individuality engage with our own in dense, sometimes fetish-like intimacy, forging sensual relationships in which matter and body resonate directly.

Thus, Murano’s path was not backward-looking but prophetic. As mentioned above, first came adhesion to the earth rather than separation. With materials clinging strangely tightly to the ground, his experiments were not nostalgic but radically contemporary. He pursued thinness, reducing matter to precarious delicacies. Thinned to that edge, materials revealed new expressions, and we developed new emotions toward them. Thinness led also to lightness, but not the kind that lifted buildings away from the earth, as at the Villa Savoye. Rather, it was a lightness rooted in the soil, unified with the land. This thinness, this lightness, sometimes drew architecture closer to clothing, erasing not only the boundary between building and ground, but also between architecture and smaller, lighter things—garments, furniture, tools. Finally, all matter encircled the body and entered into dense dialogue with it.

Murano even sought to dissolve the boundary between light and matter. Paper and fabric combined skillfully with light, producing a realm indistinguishable from either. Even unusual substances like luminous shells were mobilized, erasing the classical division of “matter” versus “light.” Murano’s works and our own may stand side by side on the same shelf. Earth, matter, light—such partitions vanish, leaving everything to tenderly wrap the delicate body, flickering in rhythm.

Much of what is considered “new” in recent architecture seems to me a repetition of these creative acts Murano pioneered. In the façades of fashion buildings, in the design of small houses and restaurants, we too have sought to thin, lighten, perforate, and collapse the boundary between light and matter. The only real difference may have been the nature of our clients. Murano’s supporters were, if anything, premodern in temperament. Ours have been post-20th-century, postmodern in constitution. Yet a hundred years from now, when only the material remains, such differences may no longer be perceptible. For me, Murano feels that close, that vivid.

(First published in MURANO TOGO: The Architecture and Interior Design, The Aesthetics of Spaces that Shape People [Official Catalog for the “Togo Murano” Exhibition], Archimedia, 2008)

NewsEvent Information – Symposium ‘On the Architecture of Togo Murano’ at the Japanese Culture House of Paris.

Kengo Kuma will give a lecture at the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris. Theme: On the Architecture of Togo Murano Date: Tuesday, February 11, 2025, 18:30-21:00 (French time) Venue: The Japan Cultural Institute in Paris, Grand Hall (101 bis quai Jacques Chirac 75015 Paris) Languages: Japanese and Fr … Read More

Kengo Kuma will give a lecture at the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris. Theme: On the Architecture of Togo Murano Date: Tuesday, February 11, 2025, 18:30-21:00 (French time) Venue: The Japan Cultural Institute in Paris, Grand Hall (101 bis quai Jacques Chirac 75015 Paris) Languages: Japanese and Fr … Read More