#18 March 1, 2019

In March 2020, I will retire from my professorship at the University of Tokyo following 12 years at the position. I recently began to wonder, ‘what would be a good way to conclude my time at Todai?’

Normally, professors reserve their last lecture as an opportunity to summarize their academic career. I wanted to avoid this, as I lecture throughout the year in various places, so it would be difficult to avoid an overlap in content with my most recent lecture in the university.

Instead, I thought to invite people who have had a great impact on me personally. I’ve gone through several turning points in my life, and these turning points were all brought about by the people I’ve come across. Some say it’s the period you encounter that determines your life, but for me it has been these meetings with a few special people that changed my life.

Fortunately, most of these people are still active so I thought it might be a good idea if we could talk to each other while both of us are in good shape. I wanted to let them know what I thought and how I was changed by them.

However, I’d feel extremely shy to hold such discussion sessions. I know them well already, and telling them formally that they’ve influenced me so much or explaining ‘your being means a lot to me’ can be quite awkward.

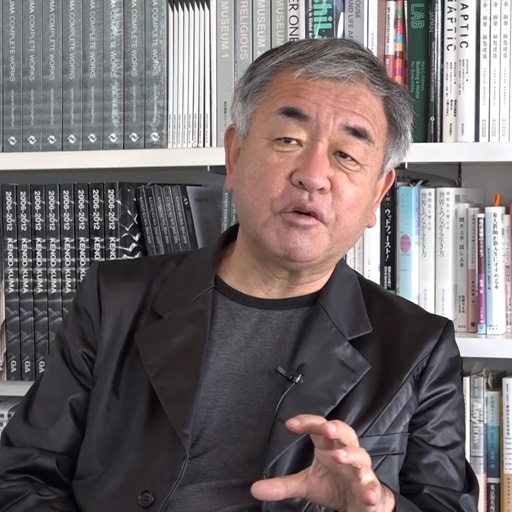

Who to invite was a good question. As I said, there have been many changes and turning points in my life, and it seemed impossible to choose just one person. I decided to hold the session ten times as “the lecture commemorating Kengo Kuma’s retirement”, which will be enough to show various aspects of myself and perhaps some of the uniqueness of our age.

For the very first session (20th April), I’ve invited Professor Hiroshi Hara, who is my teacher and mentor. I entered university in 1973 with a sense of dissatisfaction toward architecture. In my youth, in the 60s, Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa were my heroes. They were both shining stars around the time of the 1964 Olympics, when Japan was rapidly growing. Everything changed however in the 70s. I didn’t find their architecture of that time appealing at all. For me they looked over-the-top, too slick and flashy. On the other hand, I couldn’t feel close to the field of traditional Japanese architecture either, as it seemed too preachy and old-fashioned.

Given this no-way-out situation, Professor Hara, driving to the most remote corners of the world to investigate small villages, was the only sign of hope to me. The "barefooted Hara" would be the teacher for me, I thought. In a normal state I would be too shy to tell him so, but I’m hoping that if it’s for the occasion to mark my leaving, we wouldn’t have to feel so embarrassed.

ProjectsSuspended Forest

The site is located at the foot of the Jura Mountains in Switzerland, close to the deep forest. We were asked to design a family house which would be part of the Jan Michalski Foundation. Its mission is to foster literary creation and the practice of reading. The house would be suspended from an exi … Read More

The site is located at the foot of the Jura Mountains in Switzerland, close to the deep forest. We were asked to design a family house which would be part of the Jan Michalski Foundation. Its mission is to foster literary creation and the practice of reading. The house would be suspended from an exi … Read MoreProjectsZuisho-Ji Temple

Zuisho-ji Temple (Minato-ku, Tokyo) is the first temple in Tokyo of the Obaku Sect, one of the Zen Buddhist schools brought to Japan by the Priest Ingen during the Edo Period. In this project, we rebuilt the priests’ quarters within the temple. Designated as jūyō bunkazai or Tangible Cultural Proper … Read More

Zuisho-ji Temple (Minato-ku, Tokyo) is the first temple in Tokyo of the Obaku Sect, one of the Zen Buddhist schools brought to Japan by the Priest Ingen during the Edo Period. In this project, we rebuilt the priests’ quarters within the temple. Designated as jūyō bunkazai or Tangible Cultural Proper … Read MoreProjectsBirch Moss Chapel

We built a small chapel in Karuizawa aiming for its presence to be blended into the nature of birch trees. By combining the steel and the trunk of the birch, we designed a structure that might be mistaken for a real birch tree. Branches of a birch are extremely thin, but we stood them at random in t … Read More

We built a small chapel in Karuizawa aiming for its presence to be blended into the nature of birch trees. By combining the steel and the trunk of the birch, we designed a structure that might be mistaken for a real birch tree. Branches of a birch are extremely thin, but we stood them at random in t … Read More